Culture Jamming

Dagny Nome

"Promotional Culture - Seminar in Intercultural Management",

Copenhagen Business School

Table of Contents

Introduction

What is Branding?

Semiotics of Branding

Brands and Individual

Identity

Culture Jamming - a War

on Brands

Inspiration - a

Line of Revolutionaries

Détournement

(Promotional)

Culture

Is

Culture Jamming Just the Current Source of Cool?

Culture

Jamming Influences Corporate Reputation and Identity

Culture Jamming is a Vector

Conclusion

Notes

References

Walking down the street I pass a Nike poster. I hardly notice it, living in the city I am

surrounded by commercial messages. But something is not right with this one. I look

again. What happened to the usual black athlete? Why is there a woman carrying a

child, in exactly the same pose as the athlete occupied in the posters I'd already seen?

And the text - it describes working conditions in Indonesian factories where Nike shoes

are made. The final message is "..so think globally before you decide it's so cool to

wear Nike." It is clearly not an ad sponsored by Nike, yet the visual layout seems the

same. That is why I at first thought it was an ad for Nike, and mentally approached it

that way. And that is why the negative message surprises me, and ultimately, why I will

remember it. But how will my behaviour, especially the one as consumer, be influenced

by a negative message about a brand I already use?

Walking down the street I pass a Nike poster. I hardly notice it, living in the city I am

surrounded by commercial messages. But something is not right with this one. I look

again. What happened to the usual black athlete? Why is there a woman carrying a

child, in exactly the same pose as the athlete occupied in the posters I'd already seen?

And the text - it describes working conditions in Indonesian factories where Nike shoes

are made. The final message is "..so think globally before you decide it's so cool to

wear Nike." It is clearly not an ad sponsored by Nike, yet the visual layout seems the

same. That is why I at first thought it was an ad for Nike, and mentally approached it

that way. And that is why the negative message surprises me, and ultimately, why I will

remember it. But how will my behaviour, especially the one as consumer, be influenced

by a negative message about a brand I already use?

A lot of people would at first glance believe they were looking at an ad for Nike, the

sportswear producer. That is part of the power of successful branding today - being

able to create an image, a feel that the consumer remembers. This parodied Nike

poster is an example of culture jamming, a practice that uses exactly this strength to

fight the brands with which it originated. A widely used term, definitions and groups that

subscribe to it abound. For some, culture jamming is more or less anything that mixes

art, parody, media and the countercultural, outsider stance(1). Current examples of this

would be the Guerrilla Girls that demonstrate outside art galleries and museums

wearing guerrilla masks to highlight the exclusion of female artists, and the fabulous

Reclaim the Streets parties taking over parts of highways and creating massive traffic

jams while they plant trees in the asphalt.

My focus will be on the forms of culture jamming that concentrate on destroying the

value of commercial brands, and I shall use the term in this sense. To understand their

function in the current promotional discourse, I shall describe the context in which they

operate, their tactics and motivation. I will mainly use The Adbusters Media Foundation

(AMF), a Canadian based culture jamming group, as an example. Finally, I will discuss

whether culture jamming as a countercultural movement can aspire to be a real threat

to corporations, even if its expression are co-opted into the brand marketing strategies.

Or does it, in fact, function as a strong visual part of a political discourse?

In order to get a grasp on culture jamming, it is important to understand how

corporations sell their products through branding. A brand is a name and/or symbol that

signals the source of a product and differentiates it from competitors. The value of a

brand is often measured in brand equity "..a set of assets (and liabilities) linked to a

brand's name and symbol that adds to (or subtracts from) the value provided by a

product or services to a firm and/or that firm's customers."(2) Brand value is a significant

contributor to the capital value of a company(3), and the value of many major

corporations' brands is far higher than the value of its physical assets(4). Building

positive brand equity is a long and costly process, and for some organisations, like

Ford and Nike, it has become the main focus of their activities(5).

Branding efforts are increasingly aimed at building the corporate brand, rather than the

product brand. Competition on a global level, fragmentation and increased complexity

of traditional markets, together with more sophisticated customers(6) are factors that

have inspired this shift, and these are in turn increasing in importance by the spread of

corporate branding. Establishing a global brand and treating the world as one market

creates economies of scale. However, due to the costs of establishing such a global

brand it makes sense to promote the corporation, which is likely to cover several

products and be useful for longer than one of its products, often soon to be replaced

with another one. An example of this would be Nike: The corporate name or its logo,

the swoosh, is visible in all promotional activities. The Nike name is then used as a

corporate universe in which the separate product brands belong, like the Air Jordan

trainer. By building a corporate brand, corporations build a brand universe, an

overarching dimension that can be used to consecrate value on the various products

and services it sells.

Branding is done through promotional activities on two levels - direct and indirect.

Direct branding is basically advertising, where the brand is the protagonist of the story.

In indirect branding, this role is seemingly given to another, outside party, but the aim is

nevertheless to promote the brand. Brian Moeran describes promotions as "a form of

bricolage, combining familiar ingredients to create novel products and events."(7)

Through such diverse promotional activities as celebrity endorsement, product

placement in films, funding various cultural events from rock festivals to car racing,

corporations have sought to have their brands associated with, and indeed seen as

representing, the cultural values represented by the activities they sponsor. Brands

increasingly sell through promoting a lifestyle, a certain way to be and feel, as

connected to the brand. Promotional activities are aimed at accumulating "symbolic

capital", that at later stage is converted into "economic capital" when consumers buy

the product(8).

But not only do corporations seek to associate their brands through sponsoring cultural

events. They also aim to take those associations out of the representational realm and

make them a lived reality through creating their own promotional activities. This is a

further sophistication of the process of accumulating "symbolic capital". It is in this spirit

we have seen the emergence of Driversfest, a Volkswagen music festival held outside

New York. Celebrities are created, not just used as endorsement; in the way that Nike

elevated Michael Jordan and promoted him as the embodiment of age-old ideals

surrounding sport. Nike also promoted these ideals within their own chain of flagship

retail stores, Nike Town, which functions both as a temple to sports and a regular retail

store. Catalogues created by clothes companies take on the look of lifestyle

magazines. Diesel has adapted this stance into the ironic, and publishes the online

magazine "It's Real - Tomorrows Truth Today", styled as a gossip paper covering the

seedy scandals surrounding Joanna, a fictional celebrity.

Marketing academics like David Aaker stress the importance of creating a brand

identity. To create positive brand equity, he claims, the brand must be defined in more

dimensions than merely as a product, most notably as personalities, like Nike "exciting,

provocative, spirited, cool, innovative, and aggressive; into health and fitness and

excellence"(9). By building such a comprehensive map of the brand, it is intended that all

communication from the corporation to its various constituencies will be coherent and

thus enforce the distinctiveness of the brand.

Using Saussure's approach to semiotics, the process Aaker is concerned with is

creating and enforcing the signifier, the mental concept related to the signified, the

physical sign(10). Applied to brands, the projected identity is the signifier and the logo is

the signified. In trying to define what the sign means to us, Saussure states that we can

only answer in the light of what the sign does not mean. According to this model of

meaning, we use the signifieds to divide reality up and categorise it in order to reach

understanding. This system of sensemaking reflects a social constructivist

epistemological viewpoint, also seen in Karl Weick's writings on sensemaking cycles as

a way of reducing equivocality in our enacted environment(11). Returning to the Nike

example, we gather that a Nike logo is given different meaning in different parts of the

world, and in different societal subcultures/groups - but the logo is recognised due to

its ubiquity.

Using Saussure's approach to semiotics, the process Aaker is concerned with is

creating and enforcing the signifier, the mental concept related to the signified, the

physical sign(10). Applied to brands, the projected identity is the signifier and the logo is

the signified. In trying to define what the sign means to us, Saussure states that we can

only answer in the light of what the sign does not mean. According to this model of

meaning, we use the signifieds to divide reality up and categorise it in order to reach

understanding. This system of sensemaking reflects a social constructivist

epistemological viewpoint, also seen in Karl Weick's writings on sensemaking cycles as

a way of reducing equivocality in our enacted environment(11). Returning to the Nike

example, we gather that a Nike logo is given different meaning in different parts of the

world, and in different societal subcultures/groups - but the logo is recognised due to

its ubiquity.

As I shall return to at a later stage, culture jammers believe that brands are a damaging

influence on our personal identities and, therefore, on society. Before we can move on

to consider such a statement, however, we have to explore whether there exists a

relationship between brands and individual identity. For the purposes of this paper, I

find it useful to apply a definition of identity that sees it as a general, if individualised,

framework for understanding oneself that is formed and sustained via social interaction.

Individuals learn to assign themselves socially constructed labels through interaction

with others, and identity is thus fundamentally a relational and comparative concept(12).

Using this definition as a starting point, I suggest that constructed brand identities

consistently projected form a fictional "other" that we also relate to and compare

ourselves with. This is particularly relevant in the case of people inhabiting urban

environments, where these brand identities are projected in abundance through

promotional messages. Brands then become part of our enacted environments, and

thus influence how we construct our identities. People living in urban environments are

surrounded by promotional messages, and I believe that in this case a dividing line

between promotional culture and culture is no longer meaningful.

Tom Vanderbilt uses the notion of the advertised life, "an emerging mode of being in

which advertising not only occupies every last negotiable public terrain, but in which it

penetrates the cognitive process, invading consciousness to such a point that one

expects and looks for advertising."(13) This mode of being has become difficult to discern,

he claims, as media have become the surroundings.

Brands have even become cult objects, and posters of advertisements are sold as hip

accessories; we carry brand names on our bodies as clothing; we use brand slogans in

our everyday speech. Some even wear brand symbols as tattoos - the Nike swoosh

has been rather popular inscribed in one's navel. In Wernick's words "..the range of

cultural phenomena which, at least as one of their functions, serve to communicate a

promotional message has become, today, virtually co-extensive with our produced

symbolic world." Branding influences our taste, which classifies us. What brands we

consume say something to others about who we are, and thus influence our identities.

The Adbusters Media Foundation (AMF) describe themselves and their goals like this;

"We are a global network of artists, writers, students, educators and entrepreneurs who

want to launch the new social activist movement of the information age. Our goal is to

galvanize resistance against those who would destroy the environment, pollute our

minds and diminish our lives. .. We want a world in which the economy and ecology

resonate in balance. We try to coax people from spectator to participant in this quest.

We want folks to get mad about corporate disinformation, injustices in the global

economy, and any industry that pollutes our physical or mental commons."(14) AMF

publishes the quarterly magazine "Adbusters" and the website www.adbusters.org, as

well as offer its services through the advertising agency Powershift, which claims only

to take on campaigns for organisations with goals corresponding to AMFs own. Kalle

Lasn runs AMF, and has recently published "Culture Jam" to explain the movement and

give instructions in how to live an uncommercialised life.

The Adbusters magazine is like an exquisitely wrapped piece of barbed wire. Thick

paper, stylish visual layout; like the jammed advertisements it resembles something it's

not - a glossy fashion or lifestyle magazine. Open it, and the barbed wire's sting is

found in articles that seek to expose the underlying tactics and tools used when

promoting brands or expound on brands' dangerous influence. The just as stylish

website contains, apart from Adbusters magazine excerpts, information on AMF

campaigns, such as the annual TV-turnoff week, and coverage on other culture

jamming activities.

Lasn cites the French avant-garde group The Situationists as his inspiration. As a

movement existing in the 50s and 60s, it was critical to the influence of the modern

media culture, or what they called the spectacle of modern life. This omnipresent

phenomenon, everything from billboards to art exhibitions to TV, refused human beings

the experience of the authentic(15). It had kidnapped our real lives. Kalle Lasn of The

Media Foundation, a Canadian-based culture jamming organisation, uses this line of

rhetoric in justifying an attack on commercial brands when he says: "Culture jamming

is, at root, just a metaphor for stopping the flow of spectacle long enough to adjust your

set." or "..breaking the syntax, and replacing it with a new one. The new syntax carries

the instructions for a whole new way of being in the world."(16)

The final goal is a cultural revolution, or in Lasn's words, "an about-face in our values,

lifestyles and institutional agendas. A reinvention of the American dream."(17) He sees

the current culture jamming movement as part of a "revolutionary continuum that

includes, .. , early punk rockers, the 60s hippie movement, ..the Situationists.., whose

chief aim was to challenge the prevailing ethos in a way that was so primal and

heartfelt it could only be true."(18) The revolution depicted by Lasn is one where the

media-consumer trance is broken, the power of corporations seriously weakened and

authenticity rediscovered. In fact, this also places culture jammers on a continuum of

youth rebelling against the status quo, where the young rebel against the old and

established before they fade into complacent middle age and in turn are challenged by

the next generation of youth.

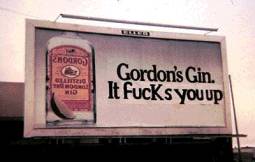

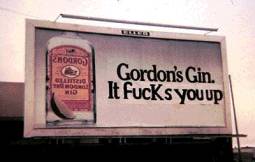

The

culture jammers of today borrow more from the Situationists, and more specifically

Guy Debord, when they speak of détournement as their main tool. The action

of détournement means to lift an image, message or artefact out of its

context to create a new meaning(19). The most

advanced culture jams are counter-messages that mimic the corporation's own

method of communication, and sends a message, a subvertisement, starkly

at odds with the one originally intended. Often, but not always, the brand name

or logo is slightly altered, but the visual recognition is still assured. The

Nike parody at the top of page 1 is a good example of this. The culture jammers

call this "a re-routing of images to reclaim them and to devalue the currency

of commercial images"(20). The Billboard Liberation

Front jams advertisement billboards, like the simple, but powerful jam on Exxon

that appeared just after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, "Shit happens - New

Exxon" or on a billboard originally advertising Gordon's Gin, "Gordon's Gin

- It Fucks You Up".

The

culture jammers of today borrow more from the Situationists, and more specifically

Guy Debord, when they speak of détournement as their main tool. The action

of détournement means to lift an image, message or artefact out of its

context to create a new meaning(19). The most

advanced culture jams are counter-messages that mimic the corporation's own

method of communication, and sends a message, a subvertisement, starkly

at odds with the one originally intended. Often, but not always, the brand name

or logo is slightly altered, but the visual recognition is still assured. The

Nike parody at the top of page 1 is a good example of this. The culture jammers

call this "a re-routing of images to reclaim them and to devalue the currency

of commercial images"(20). The Billboard Liberation

Front jams advertisement billboards, like the simple, but powerful jam on Exxon

that appeared just after the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, "Shit happens - New

Exxon" or on a billboard originally advertising Gordon's Gin, "Gordon's Gin

- It Fucks You Up".

Using Saussure's framework, this can be explained as adding negative messages to

the sign's signifier, and the goal is that consumers will include these messages when

they go through their sensemaking cycles. Promotion transfers meaning on to a product

from the outside(21) and it is this process that the culture jamming seeks to enter, by

jamming the original coherence between the message sent through product design,

packaging and promotional messages. The acts of culture jamming are thus intended to

throw a spanner into the integrated system of production/promotion which, by the

corporations, are deployed together in a mutually referring and self-confirming way.

The culture jammers believe that the consumer culture where brands live has been

allowed to occupy too much space in our lives. They believe that this influence is

damaging, and paint a bleak picture of feeble consumers standing by while

corporations are taking over the world; "American culture is no longer created by the

people. Our stories, .. are now told by distant corporations with something to sell as

well as something to tell. Brands, products, fashions, celebrities, entertainments - the

spectacles that surround the production of culture - are our culture now. Our role is

mostly to listen and watch - and then, based on what we have heard and seen, to

buy."(22), and state the need for a return to authenticity, a second American revolution.

Culture is thus elevated to something pure, almost mythical, which is being soiled by

the intrusion of commerciality. Wernick states that promotion must be defined not by

what it says, but by what it does. And what promotion does, according to Wernick, is to

force the entry of the economic world into the cultural, and thereby devaluing the latter.

His view thus reflects that of the culture jammers.

Promoting a brand can be seen as a cycle. Brands are promoting, and promoted,

through cultural references, which in turn influence our perceived realities and

behaviour. In Paul du Gay's words, this is "labelling from above". Just as crucial is "the

actual behaviour of those so labelled", which leads our attention to how we as

consumers engage with brands. Through consumption, meaning is altered(23).

Proponents of what we can call ironic consumption think that meaning is drastically

changed through how a product is consumed. This, then, is supposed to deny the

power of the values and lifestyle promoted by the brand. At the core, however, lies the

undeniable truth that as long as the product is consumed, revenue is created for the

producer. And as the consumer imbues the product with new meaning, he becomes a

producer of meaning that the original producer then consumes. The wheel continues to

turn.

The culture jammers see themselves as part of a revolutionary continuum. This is a

crucial part of what Tom Franks calls the co-optation theory; "faith in the revolutionary

potential of "authentic" counterculture combined with the notion that business mimics

and mass-produces fake counterculture in order to cash in on a particular demographic

and to subvert the great threat that "real" counterculture represents."(24) Through co-optation, therefore, we get a cultural perpetual motion machine, where corporations

feed off countercultural trends in order to sell their brands.

What once was counterculture is now abundant in advertisements. "Never Work", "It is

Forbidden to Forbid" and "Take your desires elsewhere" - all subversive messages in

the sixties(25), sound eerily like Sprite's "Image is Nothing" and countless others. What

was once the main enemy - the conformity ridden Company Man, was quickly used in

marketing and management fashions alike. "Don't liberate me - I'll take care of that",

again graffiti from the sixties, has the ring of neo-human relations rhetoric on fostering

entrepreneurialism within corporations.(26)

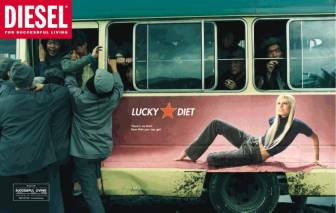

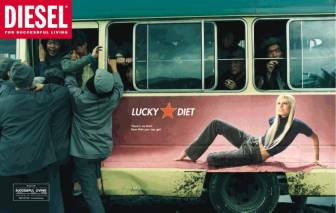

So the cultural jammers of today have moved on. They attack the communication of

corporations. It is easy to simply say - so what? The ironic stance they take is already

co-opted in advertising, which has become pre-jammed. One of the popular tools of

culture jammers is juxtaposing First World icons with Third World scenes to highlight

inequalities caused by globalisation, as in the Nike jam on page 1. Diesel jeans uses

this technique in promoting itself through the fictional Brand 0. Ads within ads, a

glamorous blonde is pictured on the side of a bus that is overflowing with frail-looking

North Korean workers. The ad is selling "Brand 0 Diet - there's no limit to how thin you

can get". Lifestyle brands are engaging in a frantic hunt for cool and hip when they buy

reports such as the L Report, sold for $20,000 a year, which presumably reveals the

current cool trends that as of yet have not been commercialised(27).

Culture jamming gets

our initial attention mostly because of the innovative way in which they use imagery,

striving to shock and provoke. In this way they are actually enlarging the amount of

expressions that are deemed acceptable by the public. What was once provoking, like

billboards of Marlboro Country superimposed on images of urban decay, now forms the

common element in Diesel's Brand 0 campaign. The use of the original technique by

culture jammers consecrated it as cool, and Diesel can now use this to their own

benefit. Seen from this angle, culture jamming is working against itself.

On top of that, the corporations will probably win out. They squash dissent by their

sheer bulk of advertising, and if anti-corporate culture jamming is only a reflection of

the current cool, it will probably change soon anyway. The Adbusters Media

Foundation is denied buying tv-time, save on CNN headlines, presumably as their

messages run counter to commercial interests(28).

There is, however, a change from earlier times' culture jamming. Earlier counterculture

movements found their main enemy in "the establishment". Such a notion could easily

be incorporated into corporate advertising, applying the revolutionary spirit in

promoting brands. Now, however, the main enemy is the brands themselves. Cultural

jammers seek to expose the oxymoronic nature of the brands and the working practices

of the corporations they represent. Even if co-opted, this focus on brands, together with

increased use of corporate branding, means that corporations are more sensitive to

public opinion. Culture jamming can be a tool to serve a higher, political purpose.

For corporations, increased interaction between "insiders" and "outsiders" through

networking, alliances and the like has lead to a boundary breakdown between internal

and external. Increased transparency has had the same effect, and has lead to a

pressure on corporations to demonstrate internal coherence with external branding(29).

Image and reputation is of greater value and the financial markets often react strongly

to negative media coverage of a corporation. Events that have a negative effect on an

organisation's reputation can also threaten the organisation's identity, which in turn

influences motivation and commitment amongst employees(30).

Nike, Disney and several other well-known brands have been strongly criticised for the

labour conditions in their overseas production facilities, most notably in Asia. Royal

Dutch/Shell has been on the receiving end of public protest because of their

involvement in Nigeria and their plans to dispose of the oilrig Brent Spar by sinking it in

the North Sea. Rather than simply do outward damage control, many corporations

claim they have taken the accusations seriously and that they have affected the way

they do business. They acknowledge the need to take public opinion into account;

human rights are included in mission statements and industry-wide labour standards

developed. The role of non-governmental organisations has changed as many function

as advisors to corporations on areas like human rights, environmentalism and labour

conditions(31). Nike, for example, publishes the results of external audits performed on

their production facilities on their corporate website, Nikebiz.

Can we influence our culture only as consumers of it? The above arguments point

towards that our roles as consumers are paramount in influencing corporations.

However, perhaps the argument can be turned around - through the role as consumer

of promotional culture we can influence areas of concern related to other aspects of our

lives. Politics enter consumerism when Nike, Reebok or Starbucks Coffee are

boycotted because of labour conditions or human rights issues related to their business

practices or the geographical location of where they do business. Culture jamming in

this case functions as a marketing tool to get attention to these political issues.

According to du Gay, meaning is created in dislocation. Dislocation is inevitable, and

occurs in our case when a projected brand identity is unable to constitute itself fully as

an objectivity. In order to be constituted as such, the brand depends on a constitutive

outside, the consumers. Put simply, a brand identity must be accepted as such by

consumers for it to be perceived as real. Du Gay calls uses the notion of vectors pulling

in different directions. This creates a dynamic process, where meaning and perceived

reality is the outcome. I have argued that the massive presence of promotional

messages can be seen as part of our perceived realities. Thus, producers and

consumers of brands are vectors. Culture jamming makes up a third. Pointing out the

presence of promotions everywhere, using marketing tools to ridicule and criticise

corporations and their brands, the rhetoric about authenticity lost - this provides a new

vector that does its best to engage in the consumer's sensemaking cycles.

Corporations

are generally reluctant to engage in conflict with the culture jammers. One reason is

that when they do, as when McDonalds took two British activists to court over an anti-McDonalds leaflet, the outcome is often bad press for the corporation regardless of the

outcome of the court case. The culture jammers are good at getting attention, as in

1992, when Absolut Vodka threatened to sue AMF over its "Absolut Nonsense" parody,

but backed down when AMF in turn went to the press and challenged Absolut Vodka to

a debate about the harmful effects of alcohol(32). Another, perhaps more important,

aspect is that the culture jammers represent the essence of what so many brands want

to be - they're cool. If corporations go after them they, and thereby the corporate

brand, would be uncool, one of the worst things to be within lifestyle branding.

reason is

that when they do, as when McDonalds took two British activists to court over an anti-McDonalds leaflet, the outcome is often bad press for the corporation regardless of the

outcome of the court case. The culture jammers are good at getting attention, as in

1992, when Absolut Vodka threatened to sue AMF over its "Absolut Nonsense" parody,

but backed down when AMF in turn went to the press and challenged Absolut Vodka to

a debate about the harmful effects of alcohol(32). Another, perhaps more important,

aspect is that the culture jammers represent the essence of what so many brands want

to be - they're cool. If corporations go after them they, and thereby the corporate

brand, would be uncool, one of the worst things to be within lifestyle branding.

On one level, culture jamming Adbusters style is branding, and it can be seen as the

marketing division of anti-corporate groups, where AMF gains credibility through its

association with other pressure groups and non-governmental organisations. The

latter, in turn, gain publicity as AMF and other related organisations grab our attention

through its strong visual focus. AMF even sells culture jamming accessories at its

website, for which it has been heavily criticised by other culture jamming groups. This

criticism is hardly a surprise, when one of the ideals AMF promotes is to lower

consumption. It also reflects a more general tendency, described by Bourdieu and

simplified here, of how the disavowal of money in creating symbolic capital leaves the

proponent wide open for criticism as it is in reality a way to create economic capital.

Thus, the ways AMF finances its operations are crucial to whether it is perceived as

"genuine".

King Solomon said, in the Ecclesiastes; "For with much wisdom comes much sorrow;

the more knowledge, the more grief." Rather than talk about the choices facing King

Solomon, I will steal his words and apply them to consumers today. Perhaps culture

jamming will alienate the consumer rather than enlist her support? If we create our

identities using brands, will we then be grateful for someone telling us how stupid we

are to be so easily seduced as when we bought those fancy Nike shoes or used the

popular anti-depressive Prozac to get rid of the winter blues? In the short term, I think

that would be too much to hope for.

Culture jamming is, however, about more than being part of the promotional discourse.

It is political, and when effective, makes consumerism political. Their main influence is

thus in the realm of corporate branding itself. When the corporate brand is paramount,

the various constituencies somehow involved with the organisation expect a higher

degree of transparency, and this in turn makes the ways in which a corporation does

business more open to outside criticism. When corporations brand themselves as

responsible corporate citizens, they are expected to behave as such. Thus, they

become more vulnerable to public opinion, and need to adjust their business practices

to the concerns of consumers. Culture jamming keeps up this pressure through their

provocative marketing and attention-seeking methods.

1.

Dery, Mark (1993) "Culture Jamming: Hacking, Slashing and Sniping at the Empire of

Signs" (Mark Dery 1993) in Klein, Naomi, p.283

2.

Aaker, David A. (1991), p.7

3.

Ohlins, Wally

4.

Aaker, David A. (1991), p.8

5.

Financial Times, 4th August 1999.

6.

Hatch, Schultz and Williamson

7.

Moeran, Brian

8.

Bourdieu, Pierre, p.76

9.

Aaker, David A.(1996) p.91

10.

Fiske, John, p.44

11.

Weick, Karl

12.

Tajfel & Turner, 1985 in David A.Whetten & Paul C. Godfrey's "Identity in

Organisations", p.19

13.

Tom Vanderbilt, The Advertised Life, in Commodify Your Dissent, p.128

14.

Presentation in "Who are we?" page on AMF homepage; www.adbusters.org

15.

Lasn, Kalle, p.101

16.

ibid p.107

17.

ibid p.88

18.

ibid p.99

19.

Debord and Wolman

20.

Lasn, Kalle, p.103

21.

Wernick, Andrew, p.16

22.

Lasn, Kalle, p.xiii

23.

du Gay, Paul, p.75

24.

Frank, Thomas (1997), p.5

25.

Julien Besançon "Les murs ont la parole"

26.

For example Peters and Waterman "In Search of Excellence"

27.

Gladwell, Malcolm

28.

Lasn, Kalle, p.32

29.

Hatch, Schultz and Williamson

30.

Dutton & Dukerich, 1991, p.517

31.

The Economist, 5.12.1998. Survey "The power of publicity".

32.

Klein, Naomi, p.288

Aaker,

David A. 1991. Building Strong Brands, New York: Free Press

Aaker,

David A. 1996. Building Stronger Brands, New York: Free Press

Besançon,

Julien 1968. Les murs ont la parole, Tchou quoted from www.slip.net/~knapp

Bourdieu,

Pierre Bourdieu 1993. The Field of Cultural Production, Cambridge: Polity

Debord and Wolman

1956. A User’s Guide to Detournement, published in "Les Lèvres

Nues #8" Belgium. Translated by Ken Knapp - www.slip.net/~knapp

Dutton,

Jane E. and Dukerich, Janet M. 1991. Keeping an Eye in the Mirror: Image and

identity in Organisational Adaptation, in Academy of Management Journal,

Vol.34, no.3.

Fiske,

John 1990. Introduction to Communication Studies, 2nd edition, London:

Routledge

Frank,

Thomas. The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and Hip

Consumerism, Chicago, University of Chicago Press

Frank,

Thomas and Weiland, Matt (eds) 1997. Commodify Your Dissent, New York:

W.W Norton and Company

du Gay,

Paul 1996, Consumption and Identity at Work, London: Sage

Gladwell,

Malcolm 1997. Annals of Fashion: The Coolhunt , New Yorker, (March 17,

1997)

Hatch,

Schultz and Williamson 1999. "Bringing the Corporation into Corporate

Branding" in The Expressive Organisation, Majken Shultz, Mary Jo

Hatch and Mogens Holten Larsen (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press

Klein,

Naomi 2000. No Logo, London: HarperCollins

Lasn,

Kalle 1999. Culture Jam – The Uncooling of America, New York: Eagle

Brook

Moeran,

Brian (ed.) 2000. Promoting Culture; the work of a Japanese advertising agency,

in Asian Media Cultures, London: Curzon/Honolulu: Hawai’i University

Press

Ohlins,

Wally 1999. "How Brands are taking over the corporation" in The

Expressive Organisation, Majken Shultz, Mary Jo Hatch and Mogens Holten

Larsen (eds), Oxford: Oxford University Press

Weick,

Karl 1969. The Social Psychology of Organizing, Reading, Mass.:

Addison-Wesley

Wernick,

Andrew 1991. Promotional Culture, London: Sage

Whetten,

David A. and Godfrey, Paul C. 1998. Identity in Organisations, California:

Sage

Walking down the street I pass a Nike poster. I hardly notice it, living in the city I am

surrounded by commercial messages. But something is not right with this one. I look

again. What happened to the usual black athlete? Why is there a woman carrying a

child, in exactly the same pose as the athlete occupied in the posters I'd already seen?

And the text - it describes working conditions in Indonesian factories where Nike shoes

are made. The final message is "..so think globally before you decide it's so cool to

wear Nike." It is clearly not an ad sponsored by Nike, yet the visual layout seems the

same. That is why I at first thought it was an ad for Nike, and mentally approached it

that way. And that is why the negative message surprises me, and ultimately, why I will

remember it. But how will my behaviour, especially the one as consumer, be influenced

by a negative message about a brand I already use?

Walking down the street I pass a Nike poster. I hardly notice it, living in the city I am

surrounded by commercial messages. But something is not right with this one. I look

again. What happened to the usual black athlete? Why is there a woman carrying a

child, in exactly the same pose as the athlete occupied in the posters I'd already seen?

And the text - it describes working conditions in Indonesian factories where Nike shoes

are made. The final message is "..so think globally before you decide it's so cool to

wear Nike." It is clearly not an ad sponsored by Nike, yet the visual layout seems the

same. That is why I at first thought it was an ad for Nike, and mentally approached it

that way. And that is why the negative message surprises me, and ultimately, why I will

remember it. But how will my behaviour, especially the one as consumer, be influenced

by a negative message about a brand I already use?

Using Saussure's approach to semiotics, the process Aaker is concerned with is

creating and enforcing the signifier, the mental concept related to the signified, the

physical sign

Using Saussure's approach to semiotics, the process Aaker is concerned with is

creating and enforcing the signifier, the mental concept related to the signified, the

physical sign

The

culture jammers of today borrow more from the Situationists, and more specifically

Guy Debord, when they speak of détournement as their main tool. The action

of détournement means to lift an image, message or artefact out of its

context to create a new meaning

The

culture jammers of today borrow more from the Situationists, and more specifically

Guy Debord, when they speak of détournement as their main tool. The action

of détournement means to lift an image, message or artefact out of its

context to create a new meaning

reason is

that when they do, as when McDonalds took two British activists to court over an anti-McDonalds leaflet, the outcome is often bad press for the corporation regardless of the

outcome of the court case. The culture jammers are good at getting attention, as in

1992, when Absolut Vodka threatened to sue AMF over its "Absolut Nonsense" parody,

but backed down when AMF in turn went to the press and challenged Absolut Vodka to

a debate about the harmful effects of alcohol

reason is

that when they do, as when McDonalds took two British activists to court over an anti-McDonalds leaflet, the outcome is often bad press for the corporation regardless of the

outcome of the court case. The culture jammers are good at getting attention, as in

1992, when Absolut Vodka threatened to sue AMF over its "Absolut Nonsense" parody,

but backed down when AMF in turn went to the press and challenged Absolut Vodka to

a debate about the harmful effects of alcohol